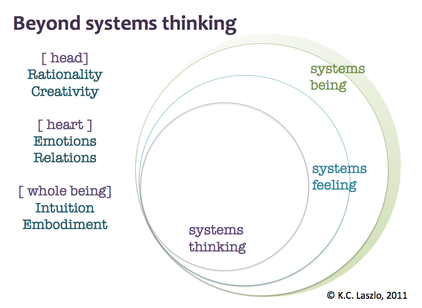

A system is a set of interconnected elements which form a whole and show properties which are properties of the whole rather than of the individual elements. This definition is valid for a cell, an organism, a society, or a galaxy. Joanna Macy says that a system is less a thing than a pattern—a pattern of organization. It consists of a dynamic flow of interactions which is non-summative, irreducible, and integrated at a new level of organization permitted by the interdependence of its parts. The word “system” derives from the Greek “synhistanai” which means “to place together.” In his seminal book Systems Thinking, Systems Practice, Peter Checkland defined systems thinking as thinking about the world through the concept of “system.” This involves thinking in terms of processes rather than structures, relationships rather than components, interconnections rather than separation. The focus of the inquiry is on the organization and the dynamics generated by the complex interaction of systems embedded in other systems and composed by other systems. From a cognitive perspective, systems thinking integrates analysis and synthesis. Natural science has been primarily reductionistic, studying the components of systems and using quantitative empirical verification. Human science, as a response to the use of positivistic methods for studying human phenomena, has embraced more holistic approaches, studying social phenomena through qualitative means to create meaning. Systems thinking bridges these two approaches by using both analysis and synthesis to create knowledge and understanding and integrating an ethical perspective. Analysis answers the ‘what’ and ‘how’ questions while synthesis answers the ‘why’ and ‘what for’ questions. By combining analysis and synthesis, systems thinking creates a rich inquiring platform for approaches such as social systems design, developed by Bela H. Banathy, and evolutionary systems design, as Alexander Laszlo and myself have developed to include a deeper understanding of a system in its larger context as well as a vision of the future for co-creating ethical innovations for sustainability. Just like the first image of Earth from outer space had a huge impact on our ability to see the unity of our planet, systems thinking is a way of seeing ourselves as part of larger interconnected systems. Most importantly, this new perception creates a new consciousness from which the possibility of a new relationship emerge: "From the moon, the Earth is so small and so fragile, and such a precious little spot in that Universe, that you can block it out with your thumb. Then you realize that on that spot, that little blue and white thing, is everything that means anything to you - all of history and music and poetry and art and death and birth and love, tears, joy, games, all of it right there on that little spot that you can cover with your thumb. And you realize from that perspective that you've changed forever, that there is something new there, that the relationship is no longer what it was." (Rusty Schweickart, Apollo 17 astronaut) Systems thinking is a gateway to seeing interconnections. Once we see a new reality, we cannot go back and ignore it. More importantly, that “seen” has an emotional connection, beautifully captured in the statement by Rusty Schweickart after his experience of seeing his home planet from space. What are the emotions evoked by perceiving for the first time the unity, interconnectedness, and relatedness of a system? What are the feelings evoked by perceiving and experiencing disconnection and isolation? Humberto Maturana says that “emotions are fundamental to what happens in all our doings” and yet, bringing up emotions in a scientific or business conversation is in many cases considered irrelevant, inappropriate or simply uncomfortable. Following Maturana’s views, I would say that the simplified answer to my two questions on the emotions evoked by unity and disconnection are love and fear, correspondingly. Love is the only emotion that expands intelligence, creativity and vision; it is the emotion that enables autonomy and responsibility. Maturana defines love as “relational behaviors through which another (a person, being, or thing) arises as a legitimate other in coexistence with oneself.” Only in a context of safety, respect and freedom to be and create (that is, a context of love) can people be relaxed and find the conditions conducive to engage in higher intelligent behaviors that uses their brain neocortex. Learning, collaboration and creativity happen when we are able to function from a consciousness capable of including a worldcentric awareness of “all of us”, as Ken Wilber puts it. On the contrary, in a situation of stress, insecurity, or any other manifestation of fear, we are conditioned to react more instinctually and to operate from our reptilian brain to fulfill more rudimentary needs linked to survival. The first image of our whole Earth from space created a sense of awe and beauty. From space, we can see (and feel) its wholeness: there are no political lines dividing our national territories, there is only one whole system. However, from our terrestrial and regionally bounded experiences, we can feel that the neighbor tribe is sufficiently different and threatening to be considered an enemy. “Before we can change the way we live, before we have saved the rainforest and the whales, we need to change ourselves. Humanity with all its different races is one. We and all other living things are nourished and sustained by the same earth” (Rema, a 14 year old girl from New Zealand). This is the leading edge of the sustainability movement: the realization that no matter how many solar panels we install, how many green products we consume, how much CO2 we remove from the atmosphere, we will not be living better lives if we do not transform ourselves, our lifestyles, choices and priorities. Sustainability is an inside job, a learning journey to live lightly, joyfully, peacefully, meaningfully. Systems being involves embodying a new consciousness, an expanded sense of self, a recognition that we cannot survive alone, that a future that works for humanity needs also to work for other species and the planet. It involves empathy and love for the greater human family and for all our relationships – plants and animals, earth and sky, ancestors and descendents, and the many peoples and beings that inhabit our Earth. This is the wisdom of many indigenous cultures around the world, this is part of the heritage that we have forgotten and we are in the process of recovering. Systems being and systems living brings it all together: linking head, heart and hands. The expression of systems being is an integration of our full human capacities. It involves rationality with reverence to the mystery of life, listening beyond words, sensing with our whole being, and expressing our authentic self in every moment of our life. The journey from systems thinking to systems being is a transformative learning process of expansion of consciousness—from awareness to embodiment. NOTE: This post is an excerpt from the plenary presentation “Beyond Systems Thinking: The role of beauty and love in the transformation of our world” by Dr. Kathia Laszlo at the 55th Meeting of the International Society for the Systems Sciences at the University of Hull, U.K., on July 21, 2011.

9 Comments

Dealing with Complexity—that’s the title of one of the foundation courses in the organizational systems program at Saybrook University that I teach. It is the introduction to systems thinking and students get an opportunity to learn the concepts and tools of how to not only understand but also identify leverage points where an intervention can make a difference. Individuals and organizations seem more able to acknowledge the increased complexity in our daily lives. It has become quite evident that the crucial problems that afflict our organizations, communities, and society at large cannot to be solved with “quick fixes.” In fact, each time we seek to address a complex problem with a simplistic approach, it backfires. And yet, learning to “deal” with complexity may be beyond the comfort zone of most people. It seems that dealing with complexity goes hand in hand with embracing uncertainty, ambiguity, constant change, and paradox. The ways of thinking and doing of the past are not very helpful anymore. The social and ecological challenges that we are facing around the globe are a perfect example of complexity—poverty, violence, injustice, water shortages, deforestation, climate change. Each problem is incredibly complex, but what makes each one complex is that the boundaries are not clearly defined. Where does poverty end and injustice begin? How is human conflict contributing to ecological degradation? Where do we begin to tackle these challenges? Many institutions decide to draw strong, arbitrary boundaries and define their purpose in a way that includes some aspects of a problem but exclude others. It is important to recognize that each time we decide to draw a boundary around an issue, we are doing so from a particular mental model that espouses certain values and assumptions. For instance, a few months ago I had the opportunity to present a project that I’m working on in Mexico to an investor group. The project involves the production of handcrafts made by inmates in a prison system who use recycled materials to create items such as purses in a fair-trade production. The business plan articulates the connection between the economic, social, and environmental dimensions of the enterprise. However, the investors strategic focus is poverty so they considered the environmental dimension of the project as “noise”—or something they don’t care about; something they think I should remove from the project. I was appalled. How could they not see the connection between poverty and the environment? I felt very strongly that their impact as social investors would be so much greater if they were able to see the systemic relationships that contribute and perpetuate poverty. It takes a systems thinker to see these connections and relationships. Systems models and maps are wonderful tools in helping us visualize “the mess,” the nickname Peter Checkland gave "complexity" in his classic book Systems Thinking, Systems Practice. That’s right: Complexity is messy. And our attempts to keep things “neat” and controllable are counterproductive when the challenge requires a transdisiplinary approach. This brings me to a reflection on dealing with complexity that is connected to the direction of my work. One thing is to perceive complexity, to map it, to identify nodes of interconnections as leverage points, and to influence the dynamics of the whole system, but this can remain a very rational and intellectual process. For us to truly learn to deal with complexity, we need to care. We need to engage our emotions, we need to be willing to perceive ourselves as part of “the mess”—not neutral observers, but actors. Unless we see ourselves embedded in this complexity—unless we accept that we are a key component of these interconnected problems—we won’t be able to be part of their solution or dissolution. Dealing with complexity involves multiple ways of knowing. It involves acknowledging the full range of our human experience and being willing to flow with the currents of change. Dealing with complexity is not an approach to solve problems, it is a way of dancing the path we call life. |

AuthorKathia Castro Laszlo, Ph.D. Archives

September 2014

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed