I have been teaching systems thinking as an approach to deal with complexity for many years. Complexity has become a catch word, something that is recognized as a part of modern life, something that should not be ignored or simplified. We have too many examples of reductionist approaches that tried to solve a problem through a technological (quick) fix to only find out that the solution had “side effects” that made the problem worse or created new problems. So acknowledging and even embracing complexity has been, in my opinion, a step in the right direction. However, there is still a sense of struggle… and a tendency to try to understand or at least make some sense of the complexity before we can “deal” with it. From a systems science perspective, there is a fascination with complexity models. All this is good and useful. However, I can’t but come back to my daily experience to reflect: What does “dealing with complexity” mean to me? Do I spend hours drawing complex models to understand the feedback loops of the mess in my life? Am I rigorous in the way I compare and contrast choices before making a decision? Not really. But something I do in a conscious way, is to trust my intuition. Intuition… that elusive way of knowing that is deeply embedded in our human ways, yet, systematically rejected and silenced. What if I don’t need to fully understand it all for me to move forward? What if my heart knows what’s best or what’s coming even if my brain cannot grasp it? What if my dream, the synchronistic encounter on the street, or the thought that seemed to come out of nowhere are sources of information as valuable as my overrated analytic capacities? And then, there is the emotional side of things. Yes, I’m (very) emotional. So even in my most sophisticated intellectual mode, I’m all feelings. This sensitivity has become an important compass for me. Rather than trying to keep it under control (good luck preventing my tears to come out if I feel like crying) I have decided to embrace it as the core of my way of knowing. It makes me more vulnerable, but also more authentic, or simply, more human. And this way of being more me is rooted in my being a woman. Even though I talk a lot about the importance of bringing back the feminine into our culture, what I'm really and deeply committed to do is to bring back our whole humanity. It just happens that the feminine side of things has been the one oppressed over centuries. As human beings, we are so complex: our biology, our culture, our history, our institutions, our personal experiences... there are so many entangled layers that inform who we are and why we show up (or not) in certain ways. I believe that the challenges that we face in organizations and communities cannot be fully understood by one single lens, by one simple, or worse, illusionary superior perspective. The gender lens is an important one, one that has been ignored for a long time, and therefore, one that deserves attention. But we need to work on the whole of the situation at once. And for me, the only way to do that is to focus on our humanity: What does it mean to be authentic and true to ourselves? What would it take for us to feel safe to express anything and everything that is in our hearts and minds? What would it take for us to see each other in our diversity while recognizing that we are deeply connected and that we all want to be loved and accepted? What if this radical acceptance of our uniqueness is a practice to heal ourselves and our world? I believe that only whole, healthy, fully human beings can create a good society. Complexity in nature is beautiful. We don’t need to “deal” with it. We can appreciate it, marvel at it, learn from it, work with it. It is only when we seek to control that complexity becomes a problem. And when complexity is a problem, it becomes exhausting and overwhelmingly hard work. I’m tired of that. What if complexity was welcomed with grace? Can we begin with some self-compassion and acknowledge our own complexity as people? with humility? with an understanding that we can never fully "deal" with anything but only attempt to make some meaning and take another step? I’m writing this piece as I prepare to celebrate my daughter’s 15th birthday. Becoming a mother has been the most transformative experience of my life. There is no question that having a child adds complexity to life! There is no book, no course, no advice that can prepare you for the task of caring for that new human life. But the challenge gets rightfully compensated with immense joy. My daughter has grown to become a highly reflexive teen… that’s what happens when a child gets systems thinkers as parents. She is keenly aware of the complexity of the world, or more accurately, of the mess we (adults) have created. And with youthful eyes, she questions: How did we forget that fun and laughter are really important? that we are all equal? that healthy food and clean air are more important than money? In her view, complexity is unnecessary complicatedness in human-created systems gone wacky. In my relationship with her, I’m keenly aware of how everything I do – or don’t – and everything I say – or don’t – contributes to the shaping of her consciousness as a young woman. Having grown in a traditional society with clearly delineated gender roles, I sometimes find myself in unknown territory when in my forties I begin to define who I truly am without cultural constrains. And although I consider myself a feminist and an advocate for equality, I also accept the distinct feminine essence of my being. So I’m going to try to deal with complexity with grace. I’m going to recognize that responding to my colleagues e-mails is as important as cooking a wholesome meal. I’m going to come back to gratefulness for the amazing blessings and incredible privilege that I have in my life every time I feel like it is too much. I’m going to take the time to smell the flowers, to love, and to create beauty every day. Because life is too precious and we miss its mystery when we think and worry too much. Even without understanding it all, even without feeling on top of it all, if I can feel peace and joy in my heart, then I know that I can dance gracefully with the complexity of the world.

2 Comments

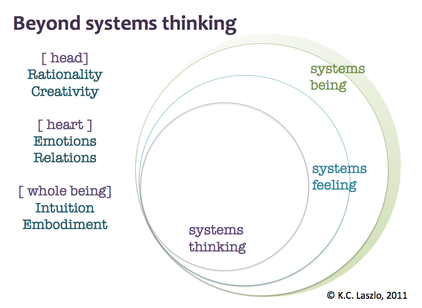

A system is a set of interconnected elements which form a whole and show properties which are properties of the whole rather than of the individual elements. This definition is valid for a cell, an organism, a society, or a galaxy. Joanna Macy says that a system is less a thing than a pattern—a pattern of organization. It consists of a dynamic flow of interactions which is non-summative, irreducible, and integrated at a new level of organization permitted by the interdependence of its parts. The word “system” derives from the Greek “synhistanai” which means “to place together.” In his seminal book Systems Thinking, Systems Practice, Peter Checkland defined systems thinking as thinking about the world through the concept of “system.” This involves thinking in terms of processes rather than structures, relationships rather than components, interconnections rather than separation. The focus of the inquiry is on the organization and the dynamics generated by the complex interaction of systems embedded in other systems and composed by other systems. From a cognitive perspective, systems thinking integrates analysis and synthesis. Natural science has been primarily reductionistic, studying the components of systems and using quantitative empirical verification. Human science, as a response to the use of positivistic methods for studying human phenomena, has embraced more holistic approaches, studying social phenomena through qualitative means to create meaning. Systems thinking bridges these two approaches by using both analysis and synthesis to create knowledge and understanding and integrating an ethical perspective. Analysis answers the ‘what’ and ‘how’ questions while synthesis answers the ‘why’ and ‘what for’ questions. By combining analysis and synthesis, systems thinking creates a rich inquiring platform for approaches such as social systems design, developed by Bela H. Banathy, and evolutionary systems design, as Alexander Laszlo and myself have developed to include a deeper understanding of a system in its larger context as well as a vision of the future for co-creating ethical innovations for sustainability. Just like the first image of Earth from outer space had a huge impact on our ability to see the unity of our planet, systems thinking is a way of seeing ourselves as part of larger interconnected systems. Most importantly, this new perception creates a new consciousness from which the possibility of a new relationship emerge: "From the moon, the Earth is so small and so fragile, and such a precious little spot in that Universe, that you can block it out with your thumb. Then you realize that on that spot, that little blue and white thing, is everything that means anything to you - all of history and music and poetry and art and death and birth and love, tears, joy, games, all of it right there on that little spot that you can cover with your thumb. And you realize from that perspective that you've changed forever, that there is something new there, that the relationship is no longer what it was." (Rusty Schweickart, Apollo 17 astronaut) Systems thinking is a gateway to seeing interconnections. Once we see a new reality, we cannot go back and ignore it. More importantly, that “seen” has an emotional connection, beautifully captured in the statement by Rusty Schweickart after his experience of seeing his home planet from space. What are the emotions evoked by perceiving for the first time the unity, interconnectedness, and relatedness of a system? What are the feelings evoked by perceiving and experiencing disconnection and isolation? Humberto Maturana says that “emotions are fundamental to what happens in all our doings” and yet, bringing up emotions in a scientific or business conversation is in many cases considered irrelevant, inappropriate or simply uncomfortable. Following Maturana’s views, I would say that the simplified answer to my two questions on the emotions evoked by unity and disconnection are love and fear, correspondingly. Love is the only emotion that expands intelligence, creativity and vision; it is the emotion that enables autonomy and responsibility. Maturana defines love as “relational behaviors through which another (a person, being, or thing) arises as a legitimate other in coexistence with oneself.” Only in a context of safety, respect and freedom to be and create (that is, a context of love) can people be relaxed and find the conditions conducive to engage in higher intelligent behaviors that uses their brain neocortex. Learning, collaboration and creativity happen when we are able to function from a consciousness capable of including a worldcentric awareness of “all of us”, as Ken Wilber puts it. On the contrary, in a situation of stress, insecurity, or any other manifestation of fear, we are conditioned to react more instinctually and to operate from our reptilian brain to fulfill more rudimentary needs linked to survival. The first image of our whole Earth from space created a sense of awe and beauty. From space, we can see (and feel) its wholeness: there are no political lines dividing our national territories, there is only one whole system. However, from our terrestrial and regionally bounded experiences, we can feel that the neighbor tribe is sufficiently different and threatening to be considered an enemy. “Before we can change the way we live, before we have saved the rainforest and the whales, we need to change ourselves. Humanity with all its different races is one. We and all other living things are nourished and sustained by the same earth” (Rema, a 14 year old girl from New Zealand). This is the leading edge of the sustainability movement: the realization that no matter how many solar panels we install, how many green products we consume, how much CO2 we remove from the atmosphere, we will not be living better lives if we do not transform ourselves, our lifestyles, choices and priorities. Sustainability is an inside job, a learning journey to live lightly, joyfully, peacefully, meaningfully. Systems being involves embodying a new consciousness, an expanded sense of self, a recognition that we cannot survive alone, that a future that works for humanity needs also to work for other species and the planet. It involves empathy and love for the greater human family and for all our relationships – plants and animals, earth and sky, ancestors and descendents, and the many peoples and beings that inhabit our Earth. This is the wisdom of many indigenous cultures around the world, this is part of the heritage that we have forgotten and we are in the process of recovering. Systems being and systems living brings it all together: linking head, heart and hands. The expression of systems being is an integration of our full human capacities. It involves rationality with reverence to the mystery of life, listening beyond words, sensing with our whole being, and expressing our authentic self in every moment of our life. The journey from systems thinking to systems being is a transformative learning process of expansion of consciousness—from awareness to embodiment. NOTE: This post is an excerpt from the plenary presentation “Beyond Systems Thinking: The role of beauty and love in the transformation of our world” by Dr. Kathia Laszlo at the 55th Meeting of the International Society for the Systems Sciences at the University of Hull, U.K., on July 21, 2011.  Dealing with Complexity—that’s the title of one of the foundation courses in the organizational systems program at Saybrook University that I teach. It is the introduction to systems thinking and students get an opportunity to learn the concepts and tools of how to not only understand but also identify leverage points where an intervention can make a difference. Individuals and organizations seem more able to acknowledge the increased complexity in our daily lives. It has become quite evident that the crucial problems that afflict our organizations, communities, and society at large cannot to be solved with “quick fixes.” In fact, each time we seek to address a complex problem with a simplistic approach, it backfires. And yet, learning to “deal” with complexity may be beyond the comfort zone of most people. It seems that dealing with complexity goes hand in hand with embracing uncertainty, ambiguity, constant change, and paradox. The ways of thinking and doing of the past are not very helpful anymore. The social and ecological challenges that we are facing around the globe are a perfect example of complexity—poverty, violence, injustice, water shortages, deforestation, climate change. Each problem is incredibly complex, but what makes each one complex is that the boundaries are not clearly defined. Where does poverty end and injustice begin? How is human conflict contributing to ecological degradation? Where do we begin to tackle these challenges? Many institutions decide to draw strong, arbitrary boundaries and define their purpose in a way that includes some aspects of a problem but exclude others. It is important to recognize that each time we decide to draw a boundary around an issue, we are doing so from a particular mental model that espouses certain values and assumptions. For instance, a few months ago I had the opportunity to present a project that I’m working on in Mexico to an investor group. The project involves the production of handcrafts made by inmates in a prison system who use recycled materials to create items such as purses in a fair-trade production. The business plan articulates the connection between the economic, social, and environmental dimensions of the enterprise. However, the investors strategic focus is poverty so they considered the environmental dimension of the project as “noise”—or something they don’t care about; something they think I should remove from the project. I was appalled. How could they not see the connection between poverty and the environment? I felt very strongly that their impact as social investors would be so much greater if they were able to see the systemic relationships that contribute and perpetuate poverty. It takes a systems thinker to see these connections and relationships. Systems models and maps are wonderful tools in helping us visualize “the mess,” the nickname Peter Checkland gave "complexity" in his classic book Systems Thinking, Systems Practice. That’s right: Complexity is messy. And our attempts to keep things “neat” and controllable are counterproductive when the challenge requires a transdisiplinary approach. This brings me to a reflection on dealing with complexity that is connected to the direction of my work. One thing is to perceive complexity, to map it, to identify nodes of interconnections as leverage points, and to influence the dynamics of the whole system, but this can remain a very rational and intellectual process. For us to truly learn to deal with complexity, we need to care. We need to engage our emotions, we need to be willing to perceive ourselves as part of “the mess”—not neutral observers, but actors. Unless we see ourselves embedded in this complexity—unless we accept that we are a key component of these interconnected problems—we won’t be able to be part of their solution or dissolution. Dealing with complexity involves multiple ways of knowing. It involves acknowledging the full range of our human experience and being willing to flow with the currents of change. Dealing with complexity is not an approach to solve problems, it is a way of dancing the path we call life. This is the title of a seminar I will be offering next week at Saybrook’s Residential Conference to launch the spring semester. I’m excited to be offering it in collaboration with my dear friend and colleague Nora Bateson who has produced a profound film about her father — the anthropologist and systems theorist Gregory Bateson. Gregory was a faculty member at Saybrook in the 70s and his work and legacy has been part of Saybrook’s educational fabric since then.

“What is the pattern that connects the crab to the lobster and the primrose to the orchid, and all of them to me, and me to you?” asked Gregory Bateson. This is one of the most beautiful statements of relational knowing. In my inquiry about systems thinking and systems being, I have discovered that relational knowing is a way of connecting my mind with other minds, my emotions to meaning making, and my interactions with other human beings as an intrinsic aspect to learning. One dimension that Nora and I will be exploring is how we are bringing to life our understanding of “the pattern that connects” as her father called it, and in which ways our experiences and perspectives as women inform our work within and beyond the systems and cybernetics scientific communities. It is our sense that we live at a time in which the notion of “an ecology of mind” is relevant not only in academic pursuits but also as a way for people to create a meaningful and purposeful life through relational knowledge and storytelling that connects, embodies and brings meaning to our fragmented world. Some of the pearls of wisdom that I have gathered from my interpretation and assimilation of Gregory Bateson’s work are:

In all the books and research papers on systems thinking that I have read, I don’t think I have yet found the word courage as part of the language used. There is a lot written about systems thinking in terms of it’s relevance and importance, it’s theories and methodologies, but nothing about what it takes–emotionally. And I’m convinced: systems thinking not only requires skill, it also takes courage.

I was invited as a keynote speaker to the 9th Brazilian Congress of Systems in Palmas, Brazil. My colleague, Raul Espejo, was the speaker who opened the conference. His presentation was about learning to act systemically. He ended his presentation with a poignant statement: “Systemic sensibility is an ethical imperative.” My presentation was the last event at the conference and I began with Espejo’s closing remark. I was happy that a recognized cybernetician like Espejo chose “sensibility” and not something else like systemic understanding (a cognitive capacity) or systemic modeling (a technical capacity), for instance. He said systemic sensibility. How perfect for me: That was the focus of my presentation– the need to move from systems thinking to systems feeling, being and doing. In one of the sessions, a researcher presented his work on the management of toxic agrochemicals using the Viable Systems Model as his methodology. Given that my Portuguese is basically non-existent, I understood very little, but enough to realize that the scope of the inquiry was very narrow. This became apparent in the Q&A session when the researcher said that as an employee of the Ministry of Agriculture he doesn’t have the power to question the use of pesticides and herbicides but only to regulate and control their use. My internal reaction was: What kind of excuse is that? He also said that he wants to feel good about his work and therefore doesn’t question the current practice of using toxic chemicals in agriculture. I was shocked. What kind of systems thinker restricts the scope of his work to the limitations imposed by reductionistic cultural practices? Two possible answers came to my mind: 1) a not-sufficiently-systemic thinker who misses the implications of his conformity to the status quo; or 2) a systems thinker who is too afraid to question the status quo. A true systems thinker will continually ask the difficult questions that expand the boundaries of the inquiry. But it takes courage to ask those big questions (usually beginning with why? and why not?) that take us to the root of a problem; where we usually find that we are an integral part of it and that change will involve changing ourselves. I wanted to ask him: Do you need clean air to breath? Do you love a child? Do you care about the health of people? What happened (or did not happen) in your education or life experience that got you disconnected from the pulse of life? How did you become more concerned about fitting into an unviable, unhealthy system than to be an agent for its transformation? When I notice that someone is acting within such self-imposed limitation; a failure to assume our common responsibilities and to own our power to change the course of human systems, something gets activated in me. I cannot remain neutral and ask curious unattached questions. I become “emotional.” It is this emotional connection that moves me, in a humble but persistent way, from being a passive observant to an active participant among initiates who know we can affect systemic change toward peace and sustainability. Whether it is through the experience of fear, despair, anger, joy, beauty, or love, I am moved to speak up on behalf of living systems and future generations. I do so because I care, because I know that what is at stake is much more than my egoic gratification, my sense of safety and comfort, or my desire to be accepted by a group who might find my words unconventional or threatening to their privilege. We hide behind walls that arbitrarily separate the disciplines and professions, and we justify our inaction by telling ourselves and others “that’s not my area.” We go around the ethical imperative to embrace a systemic sensibility, to be fully human, and to assume our role as leaders. We overlook the fact that our thinking, our actions, the way we relate to others, and the choices we make at home, at work, or as citizens affect not only our personal lives but also the possibilities for the future of this interconnected planet. However, the idea that everything is connected to everything is not an abstract concept. It is a very practical guide for how to live! There was no lack of passion in this conference. Oh no. Even though many of the presentations involved content that was highly theoretical or conceptual, the presenters clearly demonstrated that systems researchers are passionate about their work. This is good: it is a testament that these inquirers find their explorations meaningful. I wonder if this passion could be the energy needed to expand the boundaries of systems inquiry and find the courage to embrace the big questions raised by most encompassing systems. Let us ask the simple but fundamental questions: So what? Who cares? Is it good for people and planet? When the results of a study or project are treated as only relevant to a narrowly defined group of technicians, without considering whether it has some undesirable “side effect” for someone else, then there is a need for courage and a heart connection to the real needs of the world. Scientific specializations should become perspectives to support the transdisciplinary exploration of larger and more fundamental questions that are relevant to humanity as a whole and the viability of our global civilization. What kind of economic system, educational system, health care system, food production system, or political system works in accordance to life-sustaining principles? The answer is: The ones we need to design. We already have the knowledge and technology to create them. Now we need the courage. My work has been grounded in systems thinking. That has been the intellectual field that has informed my inquiry and has justified my natural tendency for connecting seemingly unrelated things and expanded boundaries. The field that has supported my personal quest for greater integration and inclusivity.

However, although I continue to do much of my work in academic environments, I’m finding the need—and the desire—to explore other ways of knowing that academia has not been too eager to embrace. We have overemphasized our intellectual abilities. But I believe that at this point in time, with the urgent and complex challenges at the local and global levels, we cannot rely only on our brains. There is a call to include the heart. Not only the heart, but also the hands and the whole body. It is time for moving beyond systems thinking and to learn to be truly systemic. We have learned much from “living systems”—those complex, adaptive, evolving natural systems that span from cells to galaxies. So it is time to learn how to live those systems, how to be those systems, how to feel those systems, and how to evolve with those systems. So I’m in experimentation mode. And I took a risk with my students. The inspiration came from my recent experience at Wasan Island, in Ontario, Canada, where the group dialogue and collaborative exploration went beyond transformative learning to collective healing. The role of creative expression was crucial in this experience. Music, movement, poetry and painting in a beautiful-beyond-words natural environment created a safe space for our full humanity to show up. The fact that this experience happened in an island was intriguing: is it so that powerful experiences, like these, are meant to be in remote places as once-in-a-lifetime events? I hope not. In fact, I had a beautiful vision: this island—and I have heard since then that many islands around the planet—are sacred places where we are able to experience the possible human (a glimpse of our future). So my exploration was about how to re-create those elements that could create the conditions for deep connections; openness and vulnerability; authenticity and joy. I think that those are good ingredients for the kind of learning we need to do. At the last Saybrook residential conference (or RC), I offered a one day workshop. I remember having a clear intention for what I wanted to do, but I was not completely clear on how to do it. My current learning is about listening deeply to what wants to emerge. I’m too used to coming up with a clear design in my mind and simply implement it. But what if there is something else that could happen in the space of my workshop if I allow it to show up? I had to submit a description for the workshop a few months before the conference. So I did. The title that I chose was “A Systems View of the World Revisited: Thinking, Emotions and Intuition to Transform Your Self and the World.” It seemed to capture (in words) my intention and it played on the concept of the “systems view,” which my mentors Ervin Laszlo and Bela H. Banathy were so instrumental in disseminating. I’m standing on their shoulders and seeking to honor their contribution. Once the final schedule of the RC was completed, I learned that my workshop would run parallel with another seminar that was a requirement for a lot of my organizational systems (or OS) students. Darn. But I was happily surprised with a fairly large group that included students not only from the OS program, but also psychology and human science. That morning, during breakfast, I finalized the flow of learning activities for the day. I wouldn’t call it improvisation unless we redefine the term. For me, it is practicing how to allow something to happen through me rather than making something happen. Of course, I was about to try to create a sacred space in the most profane environment (a hotel conference room). I couldn’t bring the pristine and enchanting nature of Wasan Island. But what I could bring was a slightly wider range of the human experience. After welcoming the group, my first announcement was that there was no power point presentation for the day – something quite revolutionary in a graduate seminar. Before we went around the circle to introduce ourselves, I facilitated a movement exercise that helped each individual to focus on themselves, then on the spaces between them, and then on each other, ending the movement (and silent) exercise with looking into the eyes of every single individual in the group. So before we talked to each other, we already felt empathically connected. The day progressed with rich dialogues to reflect on the experiences, make connections to our personal and professional journeys, and playing to put in practice some of the concepts we were exploring to real organizational or community cases offered by students. We were practicing collective intelligence. After lunch, I told the group that it was OK if anyone preferred not to participate in the afternoon session of the workshop. They had permission to leave or to only observe. I took out water crayons and gave them paper to draw. They had to do it on the floor sharing the crayons and using their fingers to smear the color with water. I asked them to paint two pictures. The first was free painting to express themselves in whatever way it was meaningful to them after the morning experience. The other painting had specific instructions—it was a shamanic exercise from the Maori medicine men of New Zealand that uses symbols to create a picture as a divination tool. This group of Ph.D. students looked like kindergarteners playing together. They even had to clean up after they finished their paintings. And, even though in OS we can be quite inclusive of emotional and even spiritual perspectives to inform our work as scholar-practitioners, I wasn’t sure if the archetypal nature of the Maori exercise was going to resonate with them. But it did. In fact, they found it deeply informative of themselves and their life path. We closed the day with a circle of appreciation. It was hard to contain my tears of joy for the beautiful experience that we co-created that day. The feedback that I received a few weeks later was interesting. In the Wasan Island experience, it was very clear that we said “yes” to an ambiguous invitation because we trusted the individuals who invited us. I think that the same happened in this RC seminar. Nobody remember the title of the workshop (not even me!) but they simply described it as “Kathia’s workshop.” Almost nobody understood what the day was going to be about from what they read in the conference program description—another indication that they trusted me. But 100 percent of the students who provided feedback expressed that the experience went beyond their expectations and that it was highly valuable. Phew! This seminar was a baby step for me. A step in my own journey to listen to my calling and to do the work that I’m called to do. The experience gave me confidence that there is interest, maybe even readiness, to start working from this place of not-knowing or of knowing differently. I am so grateful for my students and for the institutional context that Saybrook provides for this kind of work. This kind of learning is possible in very few places. Saybrook is still one of those special places.  I attended the International Society for the Systems Sciences (or ISSS) conference this summer in San Jose, California, and I was fortunate to share the experience with a dear group of students and collaborators. I have been part of ISSS since 1999 and this scholarly community has been part of my “intellectual family.” Each year, in addition to the knowledge and insights that come from such a rich collection of plenaries, paper sessions and workshops, I find a lot of value in the re-encounter of friends and colleagues. This year had a particular twist for me—a feminist twist. In the last few years, I have been seeking my own voice within the systems community. I have noticed some gaps and omissions. I have discovered that the discourse of systems thinking is not sufficiently systemic—yet. My bias comes from my culture and my gender. Being a Mexican woman means many things to me, but within the systems community, it means that I come from outside the boundaries of the origin of this scientific movement, which is at its core male and European. Last year, at the meeting in Hull, England, I gave a plenary talk titled “Beyond Systems Thinking: The Role of Love and Beauty in the Transformation of Our World.” The ISSS community is diverse, but I definitely felt that I went beyond the limits of what is considered “scientific” by some. Not surprisingly, those who expressed appreciation for my ideas were primarily women. ISSS was founded in 1954 as the Society for General Systems Research by Ludwig von Bertalanffy, Anatol Rapoport, Ralph Gerard and Kenneth Boulding. Boulding served as its first president in 1957. For the next 48 years, all the presidents of the society where white males with the exception of Margaret Mead in 1972. In 2005, Debora Hammond became the second female president. Since then, we have had two more female presidents: Allena Leonard in 2009 and Jennifer Wilby in 2011. Although this is a good sign, there is still an imbalance in gender representation to put it mildly. Regardless of this, there are many feminine voices within the systems community that have contributed in significant ways to the society and the field. There are two aspects that intrigue me about the role of women in the systems movement. First, the integration of feminine ways of knowing in the structures and processes that we use to conduct systems research and to share and learn from each other. A prime example of this was the conference organized by Debora Hammond in Sonoma State University. I had the opportunity to collaborate with her and a diverse team that she brought together to design the conference. Debora introduced several innovations: a strong connection between the global relevance of the annual conference with the current trends at the local community level, the integration of creative and artistic expressions as key components of the conference activities, and more participatory and dialogue-based processes to encourage collaboration and synergy. The experience of the Sonoma conference inspired future conferences, such as the one in 2010 in Brisbane, Australia, where the organizing committee created a progressive plenary that involved field trips to integrate an experiential component to the keynote sessions. At its core though, the ISSS conference remains fairly traditional. The concept of the “week-long coffee break” conceived by past president Bela H. Banathy, Sr., and fully embraced in the bi-annual conversation events sponsored by the International Federation of Systems Research in Austria, has remained a peripheral approach for ISSS. There are many other professional associations that have fully adopted “unconference” format as a recognition that the desire to establish meaningful connections and learn interactively from each other is what brings people together. The other aspect related to the role of women in the systems movement is the urgent need to balance the under-represented feminine perspective. There are many female systems scientists that need to be honored and recognized. The legacy of women in the community is important to encourage the new generations of systems scientists—both men and women—who will bring unique and diverse perspectives to evolve the field. The move toward a more holistic science will require the integration of the masculine and feminine; the rational and intuitive; the intellectual and creative. A true systems science will include the whole of the human experience and the inclusion of more female voices is just a first step in the process of embracing the rich and diverse perspectives from the peoples of the world. It is time for systems science to translate ideas into actions; to connect minds, hearts and hands so that systems science can support the conscious evolution of humanity. Last week, I had the opportunity to fly for the first time in my life—and maybe the only one—in a hot air balloon with my daughter, Kahlia. I got the tickets last year at her school’s auction. The combination of planning a special outing while helping our beloved charter school made sense. We have tried to schedule this trip on several occasions since last summer, but each time we tried the weather was not right. Finally, last week was our chance.

We had to be at the Sonoma County Airport at 5:30 a.m. just before sunrise. Too early for this mother-daughter duo who self-identify as night owls, but it was part of the adventure. The moon was still bright, but we could see the first rays of sunlight shining. After checking in, we got in the van that was pulling the trailer with the basket of our balloon and we went to the launching site. We watched how they first inflated the balloon with cold air and then filled it with hot air from the burners to lift the balloon. There were four other balloons preparing to fly that morning so it was nice to experience the set up of our own balloon and also see when the others were up and ready to depart. We jumped into the basket and, pretty soon, we started to ascend in the most gentle way. Then voilá! Minutes later, we were seeing the world from a completely new perspective. The beautiful colors of the sky, the magical sight of the other balloons floating around us, and the views of the vineyards and mountains in the horizon made the journey feel like a dream. One of the most exciting moments for my daughter was to be able to spot jack rabbits hopping across the fields below us—something you can’t do from an airplane window! “That’s the way a hawk sees its pray,” Kahlia said. It was in that moment that I realized that my daughter was getting an experiential “systems thinking” lesson. From then on, I couldn’t help but make comments to point out the uniqueness of this privileged perspective. My mentor Bela Banathy, Sr., developed an approach to develop a systems view which consists of three models: the functions, or structure model; the process model; and the system environment model. Describing a system using these three models creates a rich picture—a comprehensive understanding of the parts, the relationships between the parts and the whole, and the relationships between the whole and its larger context. Bela described the system environment model as the “bird’s eye view,” or an expanded perspective that enables the observer to appreciate the whole picture. The beauty of the bird’s eye view is that it is the systemic perspective that takes us beyond rationality because, when we see the whole picture, we can’t avoid feeling awe. Bela was also fond of making his students simplify complex ideas by asking, “How would you explain it to a 13-year-old?” Since that’s my daughter’s age, this ballooning adventure turned out to be a perfect learning opportunity for both of us. This systems view allowed us to see the patterns of the landscape that are hidden from our day-to-day, on-the-ground perspective. We could see how lush, green and diverse the areas with natural forest were; the curiously artificial straight lines of the grape fields; and how the barren fields, waiting to be cultivated, looked like scars on the earth’s surface. Also, from this perspective, we could see how poverty and wealth differ. We saw houses surrounded by junk yards and mansions with manicured gardens, swimming pools, and multiple luxury cars parked outside. We noticed the contrast between two adjacent neighborhoods, separated by a small creek: on one side, trailer homes; on the other, a gated community with large houses. My daughter and I commented on the big difference of these two communities separated by such a thin natural boundary. But from up there, it was very clear: there are no real divisions. People working in the fields stopped working to wave at us. A family came out of their house to see the balloons and to shout, “Good morning.” There have been occasions when I’ve seen a hot air balloon in the air while driving my daughter to school and thought, “I wish I was up there.” There is a very human yearning—to see the world from a higher place. It removes us from the ordinary and helps us appreciate life. Once in a while, we should allow ourselves to fly, to get to higher ground, and to take a deep breath and absorb the majesty of the world and our place in it. I completely believe in “the power of intention to spark evolutionary change,” as my colleague Nancy Southern so eloquently expressed it.

As human beings, we have the capacity to envision a different future and to commit to actions that will turn that vision into a new reality. That’s the power of systems design: the power of coming together to dream and learn, to empower ourselves, to collaborate and transform our realities. In the sustainability field, we face the challenge of extreme complexity and gloom scenarios. We hear mainly bad news: scarcity and decline. It is extremely easy for people to feel overwhelmed or depressed. We find ourselves living in fear and fear inhibits the creative response required. My work in the sustainability field has been focused on developing individual and collective capacities for this creative response. Systems thinking, collaborative learning and dialogue, leadership and communication skills, ecological literacy and design competencies are some of the practices that empower groups to work effectively on socio-ecological issues. However, there are some subtle distinctions that I have learned to appreciate. There is a difference between making things happen and allowing something to emerge. The first is a more “technical” approach. The second a more “co-creative” one. Is sustainability something to build or a garden to cultivate? A destination to reach or a path to dance? Here are some of my reflections to move in this direction. From thinking to being Thinking is good. We need more critical, creative, and systemic thinking. We need to engage our whole brain to deal with complexity. But thinking is just the beginning. Unless we are able to feel and live in new ways, we won’t be able to manifest new realities. From intellectual knowing to multiple ways of knowing Since the scientific revolution, we have placed Cartesian knowledge above other forms of making sense of our human experience. I think we are at a point in our evolutionary development when we are ready to integrate some of the wisdom that we lost. We need to learn from equations and poetry; scientists and spiritual leaders; industrialized and indigenous cultures; men and women; peoples of all colors, shapes and orientations; children and elders; our ancestors and the unborn generations; and from our connection with the land and the stars. Our history has provided us with all the knowledge we need to create our future. It is time to harvest the lessons and to put them into practice. From words to emotions I am passionate about dialogue and have experienced its transformative power many times. A learning conversation is a form of action. This is true when we engage with each other beyond words and concepts; when we listen with the heart and not only with the ears. If we are trying to inform and educate, if we are trying to connect and engage multiple stakeholders in our efforts, we need to make sure we communicate care, humility, and compassion, even if we don’t mention these words. And we need to make sure we deeply listed and consider their own cares and concerns. From “me” to “we" There’s a lot of lip service concerning collaboration when, in reality, we are still functioning in individualistic ways. There are thousands of organizations around the world working on water issues, but most of them remain as isolated efforts. Even though we are starting to become more aware, and even understand, that we are deeply interconnected, our actions don’t reflect this fact yet. It’s time to truly come together and to intentionally create synergies. If there is one global solution to the sustainability challenges, it’s a solution that includes us all—all living beings on this planet. |

AuthorKathia Castro Laszlo, Ph.D. Archives

September 2014

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed