It is inspiring to see more and more social enterprises been created. Social entrepreneurs are innovating new structures to integrate business knowledge with a socio-ecological purpose, expanding what traditionally has been considered profit. At the same time, the experimentation with new structures and processes also means that social entrepreneurs have to walk a tight rope between the expectations from investors and other stakeholders and their ideals of having a positive impact in the world. We are living in interesting times and there are signs that the old structures are dying. And yet, creating the organizations of the future require that we hold the creative tension between the old and the new, between the known and the unknown. It is a delicate balance, but much learning can be derived if we do this work in a conscious and reflective way. For example, we know that we desperately need a new educational system that responds to the needs of the future we desire rather than continue to prepare workers for the industrial age. The educational system was created as a response to increasing worker needs. In today’s global context, even the concept of “knowledge workers” is passé because we cannot continue to think of business objectives as separate from social and environmental challenges. Our world needs knowledge citizens: fully engaged human beings, ready to learn throughout their lifetime and to connect their personal passion with the work they do. Organizations cannot limit themselves to attract the best talent. Once they have highly intelligent and creative people, leaders need to create the conditions in their organizations to retain that talent and to engage them in new and deeper ways. New generations are not willing to split their lives: it doesn’t make sense to them to make a living in one place and make a life somewhere else. Meaning and connection are becoming as important as fair remuneration. Shared vision and even shared ownership of the organization are becoming more relevant for the success of social enterprises. I have observed three levels of employee engagement that distinguishes “business as usual” organizations from “mission-driven” organizations: First level: Transactional The leaders of the organization seek to attract talent according to the technical and business skills required for the success of the enterprise. The relationship between the employer and employees is transactional since it is primarily based on an exchange of knowledge and skills for a salary. People who join an organization see this relationship as a job to support themselves and their families, a means of livelihood, but they keep their personal values and aspirations separate from their professional engagement. Employees need to seek other contexts where they can express their full selves, such as in their families, communities and volunteer organizations, but at work, they are just there to do what they are asked to do. Second level: Alignment The leaders of the organization seek to attract not only competent people, but also people who might care for the purpose of the organization. The organizational values are explicit and are used to create commitment and to motivate employees to contribute to the development of the organization. Employees see their work as an opportunity to express themselves, as an outlet for living their values, fulfilling their higher purpose, and creatively contribute to something they care about. At this level, the organization sets the attractor of a mission in order to seek people that resonates with it. Employees that do not align with this organizational mission can either function at the transactional level or can choose to leave the organization in search for a better match with their values. Third level: Co-creation The leadership of the organization attracts competent and caring talent with a strong emphasis on alignment of values since their purpose is to create a mission-driven organization. Through active inquiry and participation, the leaders, employees, and other stakeholders seek to contribute and enrich the mission of the organization and support its evolution. In other words, employees do not simply adapt themselves to the organization’s mission, but the organization is open to evolve its mission based on dialogue and active inquiry that explores the overlap and synergy with the personal mission of those who are part of it. As a result, the future development of the organization at this level emerges from the co-creation of meaning that enables the fulfillment of the individuals’ higher purpose and the accomplishment of the organizational mission. Both the individuals in the organization and the overall organization may modify their values and purpose since their relationships involve a learning that supports their mutual evolution. In my experience, we have very few organizational experiences at the co-creative level because it requires an ability from the entrepreneurs and leaders to let go of control and allow their original vision to evolve. This is both difficult and risky and cannot occur without a true sense of shared ownership and shared responsibility for the protection of the integrity of the original mission. This, in my opinion, is one of the learning edges of the sustainability movement.

1 Comment

Systemic sustainability is a process of development—individual, organizational, or societal—involving an adaptive strategy of emergence that ensures the evolutionary maintenance of an increasingly robust and supportive environment. Systemic sustainability goes beyond the triple bottom line and embraces “the possibility that human and other forms of life will flourish on the Earth forever” as beautifully expressed by John Ehrenfeld. Adam Werbach defines a sustainable business as one capable of “thriving in perpetuity.” Systemic sustainability is about developing this capacity so that all human systems can co-exist in partnership with the living systems of our planet.

Systemic sustainability starts with each individual in an organization or community. It recognizes that change happens through us. Integrating systemic sustainability into the cultural fabric of an organization requires the development of practices at least four levels of intentional action. They are:

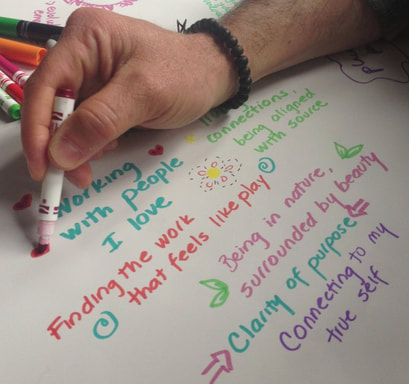

These practices make clear that sustainability—at the personal, organizational, societal, or planetary level—is a journey, not a destination; an inquiry, not a state to achieve.  In another blog post I talked about my role as an integrator. My work as a scholar-practitioner has been grounded in evolutionary systems theory, transformative learning, and systemic action-research. My most creative contributions to organizations come from my ability to question and expand perceived boundaries and from connecting seemingly unrelated “dots.” In other words, my work is about innovation as in the creation of new possibilities from the integration of disparate dimensions. I do a lot of work with social entrepreneurs: individuals committed to create social enterprises (for-profit, non-profit or a combination) that combines best business practices with values-based leadership, and with a commitment to the triple bottom line (people, planet and profit) or some other expanded metric for socio-ecological value and corporate responsibility. Over the years of supporting many individuals with the passion and courage to create social enterprises, I have noticed that the field of social entrepreneurship still embraces an old assumption: the enterprise depends on the passion and capacities of the individual leader as a “hero.” As a result, social enterprises can be strongly associated with the ego and identity of the individual entrepreneur. The failure or success of the enterprise depends on his or her capacity to overcome the enormous challenges of a new venture. After a few decades of definition and growth of the social entrepreneurship field, we are starting to perceive some of its limitations. Two that come to mind are relatively the narrow focus of social enterprises and the lack of collaboration among social entrepreneurs/enterprises – both derived from the financial pressure, competitive landscape and other practicalities of running a successful business. So the solution to world hunger gets reduced to a protein bar for an African country, or the solution to climate change would seem to depend on one (brilliant) patented new technology. The combination of these two limitations, in my opinion, have prevented a deeper and faster positive impact in the world. The good news is that every day there are more and more entrepreneurs who want to live their values and create good for the world. We are starting to see a more systemic approach to entrepreneurship: cultural entrepreneurship. Curtney Martin and Lisa Witter distinguished cultural from social entrepreneurship by pointing out that cultural entrepreneurship disrupts belief systems. I would add that cultural entrepreneurs recognize the complexity of systemic global problems. Cultural entrepreneurs are more interested in addressing the paradigmatic changes that need to occur to reinvent society. Their work contributes to a shift in consciousness, not only in behaviors. They recognize that they cannot solve these problems alone, so there is an awareness for the need of collaboration. I was interviewed by Saybrook graduate Ani Davidsen. She has a radio show called “Legacy of Change” which covers diverse topics about social change. In my conversation with her, I talked about my work as a social and cultural entrepreneur and the role of personal development and collaboration. You can listen to the interview here.  These days, I find myself eager for spaces designed for emergence. I think I have graduated from the “pretend to be in control” stage and I’m now getting acquainted to the “be ready to be surprised” stage. My life’s philosophy has always been: everything is learning. But now, I have an intense awareness that every moment, and each encounter, is a gift from the universe to support my evolution. I got an invitation to participate in this year’s Chautauqua at Mt. Madonna Center, in the Santa Cruz Mountains. The invitation was sufficiently vague to awaken my curiosity and my willingness to practice my intuition. Even though there were several reasons why staying at home and “getting things done” was really attractive, I decided that three days in nature and community could only bring me good. Saying yes involved the paradoxical combination of going with no expectations while simultaneously deeply knowing that it was going to be awesome. Although I have heard of other Chautauquas, I really didn’t know much about the spirit behind these gatherings. It was in Chautauqua, New York, in the late 18th and early 19thcenturies, where the Chautauqua movement for adult education began as a way to bring culture, entertainment and learning to rural communities. Since then, the tradition has evolved in different manifestations that continue to celebrate learning, art and community. This was the 9th Chautauqua at Mt. Madonna Center, and it was after I got there that I learned that their first Chautauqua was a creative alternative to a board meeting for the Mt. Madonna School. Ah… nothing like rebelling against the status quo to reconnect to a path with heart! The invitation included a question as preparation for the gathering: “What is it that you really, really care about in your in life and role as an educator?” That was the first clue that this invitation was meant for me. A similar question has been very present for me in the last few months. If there is one word that describes my vocation it would be “educator.” And yet, sometimes I struggle with its traditional interpretation deeply linked to formal academia. First of all, I don’t consider myself a “teacher.” I do notenjoy teaching – in the literal sense. I don’t like to be in front of a room talking to a group. I don’t feel that’s a good use of anyone’s time. In this day and age, I’m convinced that knowledge and information can be freely accessed through the web – from TED talks to YouTube videos to blogs and millions of other online resources. But mainly, I don’t think I have anything more important to share than anyone else. So spending more time talking than listening makes no sense to me. For me, education happens in relationship, through dialogue, in circle, and not in a one way presentation mode. Even in more innovative academic programs, sometimes what starts as an ambitious transformative learning ideal ends up been constrained by the structure, requirements, extrinsic incentives and the cultural inertia of academia. It is difficult to fit real world relevance into the neatness of the academic calendar or to fully allow a learning process to unfold without defining beforehand what will be the outcome. Saybrook University has been a kind of an academic oasis for me. Because of the adult learning philosophy and the research orientation, I feel I can partner with my students in meaningful explorations that are connected to their deepest cares and concerns. More often than not, I have noticed that Saybrook students manage to integrate their learning inquiries with some essential aspect of their personal healing and transformation. So I feel very fortunate to have one foot in this kind of academia – the alternative academia that has heart and that seeks to connect learners with their callings. Beyond my formal teaching and advising, I also consider myself an educator when I engage in work that involves facilitating, consulting, or coaching. The etymological root of educator is educare which means to elicit, evoke or lead out: a function more akin to gardening since it involves creating the conditions for the goodness of the human spirit to blossom. The Mt. Madonna Chautauqua was a gathering of this kind of educators. A coming together in circle – all equal, interconnected in our diversity, creating sacred space and wholeness. I love gatherings of heartfelt people. I love sitting in community and engaging in dialogue. I love coming together to learn, reflect, and be. The (very flexible and fuzzy) agenda for the three-day Chautauqua was structured around the hero’s journey: The Call, The Journey, The Return. One of the sessions during the first day was: Endings and New Beginnings in the context of the hero’s journey. That’s all I needed to know for me to come. Although the Chautauqua Design Team managed to sketch a full agenda for the three days, I knew that this was going to be an experience of listening to what wants to emerge. I was right. This was a group ready to ditch a pre-designed agenda in order to honor what needs to be honored in the moment. I walked into a room full of new faces. I was greeted with a huge smile that deeply communicated “I’m glad you are here.” Every single individual I met was a breath of fresh air: this was a space in which we could show up authentically. The group was beautifully diverse, but the spice of the gathering was the presence of youth: students from the Mt. Madonna High School. Their voices and experiences filled us all with hope and validated my commitment to humanistic education. The three days flowed like water: from whole circle dialogue to small group conversations, from singing to silence, from thinking to creating collages, from sitting to walking, from sharing to listening. Work, learning and play all at once. And although the experience was completely joyful and relaxed, it was also intense and deep. There was an abundance of knowledge and wisdom, and yet, the power of the experience was in its healing and regenerative quality. This power resides within each of us. True education is not about transmitting information – we have known that for a long time – but about creating safe spaces in which we can be ourselves and share our dreams and concerns, our ideas and questions. Access to information is ubiquitous. But freedom to be and the support to learn to love learning is such a rare thing. In a world distracted by overstimulation and enamored with technological fixes, reclaiming education as a deeply human experience seems almost impossible. In a world rushing towards catastrophe, slowing down to connect with each other seems paradoxical. Those of us who think of ourselves as educators have the simple, and yet complex, task of creating space for the unfolding of the whole human in each and everyone one of us – and for the weaving of the bonds that will enable genuine collaboration. My journey has been about integration. The Mt. Madonna Chautauqua was a kind of a ritual to recognize my “return” from one cycle in my hero’s journey: a return to reconnect with my roots, to integrate my light and shadow, and to re-imagine myself as an educator through everything I do. The return involves reconnecting to community: after gathering the lessons from our unique journeys, this is the time to come back together, to share what we learned, and to join efforts. With deep appreciation to all the participants of the 9th Mt. Madonna Chautauqua.  Imagine a different world. Imagine a world where we can solve all the problems that plague humanity. Imagine a world where we learn how to live within the limits of our planet and co-exist in harmony with all living creatures. Imagine a world with new organizations and new cultures that honor our individual gifts and soul paths, and celebrate our unique contributions to create meaningful, joyful, wholesome lives. Imagine a world with a new, sustainable, and just economy that provides for everyone without damaging the environment or that enhances the possibilities of future generations to live full happy lives. Imagine. After my first 30 minutes at the National Bioneers Conference, I was already inspired. I was surrounded by people—lots of people—who imagine these possibilities, like I do. And even better: we are all working on making this dream a reality. And while in the past we may have been called “idealists,” I think that we now feel how these ideals are attainable—even if I don’t get to see them manifested in our lifetime. We have made huge progress as a movement and there is so much more work to do: The knowledge is not yet fully distributed. We are not fully connected. We are not collaborating sufficiently or at the level that a socio-cultural breakthrough will require. We gather in conferences and events, like Bioneers, to get some glimpses of the human magnificence emerging, to recharge our batteries, to learn from each other, and to remember (and feel) that we are not alone. In her welcome message, Nina Simons, co-CEO and co-founder of Bioneers, said: “We are all called to be mothers now… to give birth to a new world.” The rekindling of the feminine in all of us—men and women alike—was a strong theme in this conference. It was a call back to wholeness, to rebalancing the power difference, to include everything and everybody, to create a world that works for all of humanity, for all of life. Nina also said: “Thank you for being here.” She probably meant for our participation and presence at this year’s National Bioneers Conference. But I understood her statement as an expression of gratefulness on behalf of all past, present, and future living beings—for us to have been born in this time of transition, for us to say “yes” and show up to do the work we are meant to do. This was my third Bioneers conference, but this year was special because I attended with my friend and mentor, Carolyn North. It was deliciously meaningful to share the experience with her. We were on the same wavelength: excited by similar things, complaining about the same things, and getting tired at the same time. We were trying to figure out if it was us or if it was the conference, but unlike previous years, the experience did not consist of just highs. There were lows too. In me, it showed up as impatience, anxiety, and nervousness. There were moments where I was pretty clear why I was feeling this way. Those moments seem to fall in two categories. The first source of frustration for me happened when I witnessed the disconnection between head and heart. No matter how visionary or inspirational the presentation was, if I couldn’t feel the presenter emotionally engaged and authentically sharing, their message didn’t reach me. However, when the people in plenaries or in panels showed their vulnerability and their humanity, their message grabbed me—and I won’t forget it. Thank you, Michael Brune, Marina Silva, Bill McKibben, DeAnthony Jones, Paul Hawken, Ilarion Merculieff, and Sharon Shay Sloan (to mention a few) for showing up authentically and humbly, for reminding us that, even though they were on stage for good reasons, they are still our companions on the same journey. They are still struggling, learning, and wondering, like the rest of us. The second source of frustration made me consider going home and it happened when I heard variations of a message that is close to my heart. We are all leaders and we are all needed, but the message was delivered in the traditional format of one person as an expert in front of the room from an elevated podium separate from the audience. I know there are logistical challenges to facilitate participatory and collaborative dialogue with hundreds of people, but if we were to acknowledge that this format is incongruent and antithetical to what we are trying to accomplish, would we continue doing it this way? I just couldn’t sit quiet for so many hours and I kept wondering why we traveled to attend the conference physically? Given the urgent need to activate our collective intelligence, I believe that if we are going to burn all the CO2 that it took to get us to the conference, we should maximize the interaction with each other and minimize the time we are talked at. I decided to also participate in a post-conference workshop called “Feminomics: How Women’s Leadership, A Gender Lens and Whole-Systems Approaches Are Re-Inventing Economics That Work for All.” Carolyn was kind to drive me there and, on the way to the workshop, she asked me, “Why are you taking this workshop?” That morning we were both feeling exhausted and quite full after three days of conferencing. “I’m not sure,” I answered. I guess it was an intuition. Yes, I’m interested in the topic and I also knew some of the presenters but, if I wouldn’t have pre-registered, I would have preferred to go home that morning. My experience in the Feminomics workshop was the highlight of Bioneers for me. Some of the missing pieces from the conference that were core to the experience of the workshop were:

I was grateful for having participated in this workshop. I think that this format could be the next evolution of Bioneers. I envision the conference becoming a series of workshops, like this one, moving the plenaries to virtual broadcasts before we get together to roll up our sleeves and engage with each other. And I envision that, in the future, the post-conference workshops will be more collaborative and action-oriented, building on the thinking that conference-goers could do together in the days leading up to them. Overall, this conference gave me an exciting and inspiring reminder: What may seem like small and insignificant actions in our individual experience can become a force for good in the world when we work collaboratively with others. There are events in your life that mark you—moments when you realize that you have learned a lesson and are ready for a new challenge. I have been working as change agent linking education, business, and sustainability together for the last 15 years. I have dedicated much of my work to creating learning communities, facilitating dialogue and collaboration, and developing leadership capacities to respond to the socio-ecological challenges and opportunities of our aching world. At the core of my work is a very human quest to find meaning in life—to align work, learning, and joy of living with a higher purpose so that we may create organizations and communities where we can be healthy, happy, and express our full potential. This past week I had the honor to participate in the Wasan Dialogue on Creative Place-Making: Recovering the Soul of Place. This learning event was sponsored by the Breuninger Foundation and took place on Wasan Island, in Ontario, Canada.

My invitation to participate in this dialogue came through my former student and Saybrook alum Julie Auger who has been an integral part of the Powers of Place initiative and actively exploring place-based leadership. Julie, Michael Jones and Volken Hann were the conveners and facilitators of this event and Dr. Helga Breuninger was our most gracious host. The invitation to be part of the Wasan dialogue was inspirational, but somewhat vague. I agreed to attend because the intention of the gathering resonated deeply within me and because I love and trust Julie. But I was aware that I was not clear what I was agreeing to and yet I had a strong intuition that this experience would be a turning point for me. Wasan means “a good place for transformation” and “for many centuries Wasan Island has been a sacred place where our First Nations contacted the ancestral world… a place of transition….” The indigenous people of this land came to Wasan to meditate and prepare to die. When I arrived to Wasan Island and met my fellow collaborators for the week, I discovered that we all came together because we knew we were ready for something most likely nobody would express in words. We said yes to something that was already alive in our hearts but that was waiting to be shared and revealed to the world. In the invitation to the event the conveners expressed some questions to guide our inquiry: “What does place have to do with transformative leadership? How can our surroundings – place, space, and environment – actively work with us as leaders to inspire and revitalize our organizations and communities? How do we know what to consider and include when creating spaces where transformative learning and action can occur? The powers of place and place-making are a critical dimension that has been largely overlooked in dialogue and leadership theory and practice. In a time when we find that strategy and tactics are not enough, the role of place, space and environment in nature, design and community are emerging as central components in revitalizing our organizations and communities as well as creating ideal conditions for creativity and innovation.” They suggested two processes as a very open and flexible structure that created the conditions for self-organization, shared leadership, and the emergence of a group consciousness. First, they requested that we prepare an ecoduction and share it with the group before we got to Wasan: “An ecoduction is a way of introducing yourself, based not on what you do for a living, who your family is, or how you spend your leisure time, but on the geographies of where you’ve come from and how this has impacted who you are now.” Second, they invited us to share “a story of some aspect of creative place-making that excites or is a source of curiosity or concern for you.” The result was a fluid and multidimensional dialogue and exploration of who we are, where we come from, and where we are going, informed by our human experiences of connecting to place and the relationships that each place—natural, cultural, imaginary—elicit. “A place is not an object or a thing, but a relationship, a power and a presence; a reminder that we can partner with place in a way that is itself deeply transformative, opening our hearts to the experience of beauty, aliveness and possibility.” Our group was delightfully diverse. Educators, researchers, consultants, managers, designers, visual and performing artists, and healers with rich backgrounds and multicultural life experiences. But in this sacred place, only our common humanity was present, and our differences were like the colors of the rainbow that came together to create beauty and joy. We learned together through sharing and listening, laughing and crying, walking and meditating, painting and creating, dancing and finding our still points. For me, we took a step beyond transformative learning into the land of healing: a return to wholeness and a re-membering—belonging again—to the sacredness of place, of community, of love. I see myself as an integrator. My work has always been about dialogue, collaboration, transformative learning and co-design. But I have learned that creating evolutionary learning communities require us to move beyond systems thinking to systems being. More and more, I’m finding the need to include creativity, emotions, and spirituality in my work because, on the path to become whole, we need to recover those aspects of our human experience that were excluded from our scientific and technological development. The time is ripe to bring back the feminine energy of love, care and beauty through our work, learning and ways of living in order to rebalance our world. During a healing meditation, I had a vision: I saw Wasan Island as a tiny piece of land in the vast majesty of our planet Earth. But from below Wasan Island came out deep roots, connecting to all the corners of our planet. I felt that my presence here, and my connection to this land, was a portal to listen to the cry of our world. I experienced personal healing, the removal of blocks and fears, in order to give back and assist in the healing of the world. The theme of healing places was very significant to me as it relates to the type of environments I’m calling to co-create. I came away from Wasan Island with a felt understanding that if we want to create spaces—communities, organizations, societies, ecosystems—where humans and nature can co-exist in harmony, we first need to inhabit healing places to enable that transition. Healing, whole, holy—three words that share the same etymological root. Healing places are sacred places, places where we can experience our full selves, without fear, without constraint. Permission to be authentic, to be fully human. During the closing circle, after this magical week together, Michael Jones talked about the call to re-enchant our world; to experience the mystery and power of the places – inside and outside – that shape us and inform all our relationships. Before my departure, I walked the perimeter of the Island once more. It was raining. The drops of rain in the water, the wind, the sound of the trees dancing with each other, the vibrancy of each plant, moss, rock—everything was alive. I realized that the world is enchanted; it has always been. It is us who are opening our eyes to this beauty. The re-enchanting of the world is about discovering this enchantment within ourselves so that we may experience oneness. Thank you Wasan Island. On May 11th, I attended the Sustainable Enterprise Conference in Rohnert Park, California. This conference has become a vibrant event in Sonoma County that fosters innovation and cultural change toward sustainability. Businesses, government and nonprofits are represented in this conference which presents both the best practices as well as the challenges ahead to create a sustainable economy and healthy community in northern California.

I have attended the conference in previous years and the program continues to be rich and energizing. It is one of those events where you can get inspiration and remember that “we are not alone” in the path to create a better future. For me, the most valuable experiences were during the breaks and transitions between sessions: it is in the unstructured spaces when I met new people, reconnected with friends and colleagues, and learned about new opportunities. During lunch, for instance, I was part of a fascinating conversation about the emerging narrative in this community: everybody is telling a piece of the story, each project, initiative, organization is contributing something to our common future. The power of coming together resides in the commitment to learn from each other, to connect and create synergy, and to start to grasp the emerging possibilities beyond our control. From an organizational systems perspective, I saw the opportunity to create more spaces for intentional dialogue. Yes, there is a lot of interaction and the event, by nature, provides wonderful networking opportunities. But what are the questions that we need to explore together? What are the lessons that are relevant for all? What are the patterns that are emerging and that can support and guide our next steps? And then, there is the challenge of transforming an annual learning event into an ongoing learning process. What can happen throughout the year, from one conference to the next, that is informed and catalyzed by the conference itself? How do we start to weave the integration of the multitude of initiatives? In a recent post on his blog “Worldshift Notebook,” Ervin Laszlo wrote: “Cooperation on the global level is a new requirement in the history of our civilization, and we are not prepared for it. Our institutions and organizations were designed to protect their own interests in competition with others; the need for them to join together in the shared interest has been limited to territorial aspirations and defense, and to economic gain in selected domains. The will to cooperate in globally cooperative projects that subordinate immediate self-interest to the vital interests of a wider community is still lacking in the political and economic domains.” The manifold sustainability initiatives in Sonoma County give me hope that we may be ready to take the risk for deep collaboration. I hope that the Sustainable Enterprise Conference continues to play a key role in creating the convergence and facilitating the synergy to curate a sustainable culture in northern California.  This semester at Saybrook University, I taught a course titled “Systems Practice for Socio-Cultural Transformation.” It was co-created with a group of organizational systems students who wanted to experience the implications of moving from systems thinking to systems being and explore other ways of working with systems tools and methodologies to facilitate transformation. As part of this learning adventure, the students organized a two-day workshop in addition to the time we had together at the beginning of the semester during Saybrook’s residential conference in January. The workshop took place in Asilomar, an inspirational conference center immersed in natural beauty in Monterey Bay, California. We used two books as key resources: The classic Systems Thinking, Systems Practice by Peter Checkland and Coming Back to Life: Practices to Reconnect Our Lives, Our Worldby Joanna Macy. We wanted to ground our learning in systemic methodologies and practices designed to facilitate change, but we wanted to do it by experimenting, adapting, and enriching the tools in ways that reflected our individual strengths and interests. I hadn’t been to Asilomar for some years but, as soon as I arrived, it was as if I was surrounded by a field of memories, emotions, and learning that I experienced there over the years. The first time I went to Asilomar was in 1993 for one of the annual conversation events sponsored by the International Systems Institute (ISI). Bela H. Banathy was the founder and president of ISI and there I met many individuals who became my dear friends, teachers, and colleagues. Here is where I decided to study with Banathy, here is where my work on evolutionary learning communities was conceived, here is where the inspiration for my organization Syntony Quest came from. The first thing I did was to visit the circular meadow in front of the registration building. I felt greeted by the Monterey cypresses in that circle. I reconnected to Bela’s spirit. Even though I didn’t know what was ahead of us in terms of the experiences for the next two days, I was already grateful. It was clear that nothing but magic was waiting for us in this gathering. The structure of the workshop was very simple: sessions of 1.5 hours in which we rotated facilitation. We were five women and each one of us brought a hands-on learning experience to explore ways of bringing systems thinking to life. The types of facilitated exercises explored issues of rank and power, compassionate communication, widening the circles when looking at challenging situations, experiencing deep empathy for others, and how to create sacred containers for emotional healing. Because of the size of the group, the experience was an easy flow from one activity to the next, and our time together during meals was equally productive and rich. We also scheduled down time to take care of ourselves and enjoy the place. This workshop was an experience of deep and transformative dialogue that allowed us to be open and vulnerable with each other, to step forward to support and care for one another, and to experience deep connections and healing. This was the most amazing aspect of this experience. As we were able to relate the ideas and exercises to our personal and professional experiences, there was a kind of group alchemy in which what we brought forth became helpful to the group as a whole. We laughed and cried together. We shared our dreams. We continued our conversations until late in front of the fire place. We all came out feeling a little bit more whole. It was very clear that the beauty of the natural environment around us was an important factor in creating such a powerful experience. Nature inspired us to be authentic, open, fluid, playful, relaxed, and diverse. I re-learned that the most important thing for facilitating systemic, socio-cultural transformation is to know and accept myself and to be fully present. By showing up authentically, in our full humanity, we discover the power to transform ourselves and our world. Self as instrument. Spending these days with this group of women was a gift. It didn’t feel like work. It was an experience of positive reciprocity: I received more than I gave. And I’m ready for more.  We have come to appreciate diversity as an asset in organizations. Diversity of gender, age, ethnicity, or any other manifestation of the ways we, as human beings, express our uniqueness. But beyond affirmative action, which creates a legal platform for equal employment opportunity, why should we care about organizational cultures that foster diversity? And how do we create them? Diversity, in biological systems, is a measure of the health of ecosystems. It produces resilience, or the capacity for the ecosystem to respond, recover from, and survive drastic changes in the environment, such as natural disasters or human disturbances. Biodiversity is not evenly distributed around the planet. Ecosystems in the tropics tend to be more diverse than ecosystems in the poles. If we see organizations as human ecosystems, we can also appreciate how different levels and kinds of diversity play a role in shaping a unique organizational cultures. Learning from the “best practices” in natural systems can be a useful strategy to reflect on the choices that we have when it comes to leadership and management challenges. Using nature as model, measure and mentor, biomimicry is becoming a popular approach for designing technologies, materials and even business processes. The learning edge of this movement, in my humble opinion, is the application of biomimicry’s life principles to the design of human systems—living, self-organizing, and evolving organizations and communities. What kind of leadership is appropriate to create and sustain a healthy and thriving culture? What’s the balance between competition and collaboration to foster the learning and innovation for evolution? What are the structures and processes that allow all members of the organization to contribute their gifts and benefit from the abundant exchange of value? These are some of the questions that guide my work. I like to experiment, observe, and reflect on the ways organizations can move away from mechanistic to living approaches to organizational development. This is the challenge that I see over and over when I work with social entrepreneurs. Their vision is beautiful and inspiring but the implementation usually suffers from “common” problems such as conflicts between partners, lack of communication, or poor organizational design. One of my current clients, a mission-driven social enterprise, has embraced the challenge of fostering a culture of diversity and participation as a reflection of their commitment to “do well by doing good.” It has not all been an easy path. Here are the three most important lessons that I have harvested so far from my experiences with social enterprises: 1. Involve all stakeholders as co-designers The most successful, beautiful, and compelling products and services that I have seen created by social enterprises were the result of deliberate co-design efforts that involved multiple stakeholders. It takes time and resources, and it is difficult for entrepreneurs to convince their investors of the value of co-design, especially at the start-up phase. However, giving stakeholders voice and engaging them in the creation of value is the best strategy for fostering a culture of collaboration. 2. Create a shared vision… and share ownership Involving multiple stakeholders as co-designers creates a shared vision and a resonant field in which all involved develop a sense of community and pride in the venture. Shared vision creates the conditions for shared responsibility and elicits creative contributions from all involved. However, if the structure of the organization concentrates power and ownership in a few individuals, as in traditional business corporations, the excitement of belonging can wither. If you want the people of your organization to feel belonging and long-term commitment to the success of the enterprise, you have to be willing to think differently about how you share decision making power and actual ownership of the enterprise. Cooperatives structures or profit sharing and stock options have a place in communicating the commitment to truly co-create the future of the organization. 3. Create the conditions for mutualism or win-win interactions The diverse species that co-exist in an ecosystem have different interactions:

A dear friend and colleague, Carlos Mota, likes to quote St. Augustine to communicate the delicate balance that allows for unity in diversity: “In essentials, unity. In non-essentials, liberty. In all things, love.” For me, this translates in agreement in vision, values, and strategy; freedom for creative exploration of the means that will make possible the vision but, above all, commitment to harmonious relationships within and without the organization for the wellbeing of the whole. As we regain perspective and, with humility, recognize our place in the intricate web of life, we discover new possibilities in the ways we go about designing and transforming organizations. There is something about human systems that makes them human: our values, intentions, and emotions. Perhaps, love for all our relations—human and biological—is the first step in the journey to innovate living organizations. I have been thinking a lot about the need for new business models. By “new” I mean truly innovative and deeply ethical—in other words, revolutionary, or even better, evolutionary.

I’m of the opinion that we have plenty of evidence and experience to harvest the lessons of what works and what doesn’t work in our current economic system and the way we engage in business. We left out too many stakeholders, too many voices, too many systems, as if they were externalities. In my quest to find out who else is thinking along these lines, I’m having conversations with a lot of people: consultants, business leaders, educators, activists, and researchers. In one conversation a few months ago, a colleague recommended the 2011 book The Responsible Business: Reimagining Sustainability and Success by Carol Sanford. I consider it one of the most exciting and systemic perspectives on the co-evolution of business and society. Corporate Social Responsibility (or CSR) could be considered a first step in the right direction, but usually CSR initiatives are, in Sanford’s language, “responsibility projects” that seek to be responsive to external expectations, standards or goals. The good news is that companies have discovered that becoming more proactive and developing strategies that weave responsibility across the organization produces better business results. But there is an additional level of responsibility where companies “can actually improve and evolve healthy systems,” according to Sanford. The responsible business understands that, as humanity, we find ourselves in a period of rapid evolutionary change and “consciously accepts the role of partner in the co-evolution of communities and living systems,” Sanford wrote. We are more used to think of organizations as machines, but it would be more accurate to see them as living organisms that adapt to and transform their environment. The interdependence between a business and the many other human and ecological systems that make possible its existence makes of any organization responsible to “more than just itself,” Sanford wrote. “It is [also] responsible to the whole of which it is a part.” Sanford proposes a systemic framework to integrate all the relevant stakeholders, as an enabling ecosystem of relationships through which the responsible business can contribute and receive value. The framework consists of a five pointed star, a pentad of five dynamic and interactive relationships that the responsible business manages to produce results. The five stakeholder groups of the pentad are: 1. Customers 2. Co-creators (or employees) 3. Earth 4. Community 5. Investors Sanford’s view of stakeholders is grounded in empathy. The responsible business is not self-centered but it’s committed to connect emotionally with these stakeholders in order to create a reciprocal relationship: a relationship that creates value for all involved. The “stake,” or care, for each stakeholder group is a source of valuable information to guide the actions of the responsible business. For example, the customers are looking for products and services that give them quality of life and the fulfillment of their purpose in life. Co-creators want opportunities to learn and contribute creatively through their work to something meaningful that’s aligned with their values. Earth’s stake is the ability to create the conditions for the ongoing flourishing of life. Communities seek healthy and vibrant participation of their members in the creation of their future, their cultural identity and connection to their place. Investors care about the lasting value that the company can generate by brand equity and customer loyalty. So all the stakeholder groups have a stake that is interdependent with the others. What I particularly like about this framework is that when we consider the stakes of each group it becomes clear that they are not separated. In society at large, the investors of a company are also customers of many other businesses, members of communities, co-creators of multiple organizations throughout their lives. And, of course, we all depend on the life supporting services of our planet. “The stakeholders comprise a living system because each is dependent on the others,” Sanford wrote. Sanford’s book is full of powerful stories of how these ideas have made a difference in large corporations. It also offers tools and guidance on how to apply the ideas in the creation of new organizations or in the transformation of existing ones. (Sanford’s website is full of downloadable resources too.) The book is a radical proposal to “reimagining sustainability and success” as its subtitle eloquently expresses. However, Sanford’s real world corporate experiences and language makes it accessible. Her vision and practice as a consultant represent an evolutionary leap in the thinking of the role of businesses in society and, yet, it makes perfect business sense. “The need for sustainability and corporate citizenship officers,” she wrote, “will simply disappear into the work of all leaders. The organizations of the future—the ones that will be able to adapt, survive, and thrive—will be systemically integrated into the fabric of society. Saying “sustainable businesses” will be redundant because, for a business to be successful, it would have to be a responsible business. Last week I had the pleasure of meeting Sanford in person and we had a wonderful, deep conversation that spanned from personal experiences to professional aspirations. I consider her a great teacher and a mentor; a woman with an incredibly sharp intellect and a generous heart. I’m inspired by her work and immensely grateful for the opportunity to share this learning path with her. |

AuthorKathia Castro Laszlo, Ph.D. Archives

August 2015

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed